Anatomy of a Poem: An Interview with R.A. Villanueva

by Ryan Lee Wong

The poet R.A. Villanueva’s Twitter handle and website are named “caesura”—a line break in a metrical foot. The name indicates Villanueva’s meticulous study of poetic forms and vocabulary. His first collection, Reliquaria (U. Nebraska Press, 2014), won the Prairie Schooner Book Prize. In it, he presents narratives of Catholic school, deep sea exploration, and art history, and transports us from the Marianas Trench to a New Jersey Catholic school to the Paris Catacombs. Throughout, the poems are made up of a solid, precise, and uncommon words. With this pastiche of vocabularies drawn from religion, science, and art, Villanueva creates for the reader a rich and dark world, full of memento moris and explorations of the vessels that carry us.

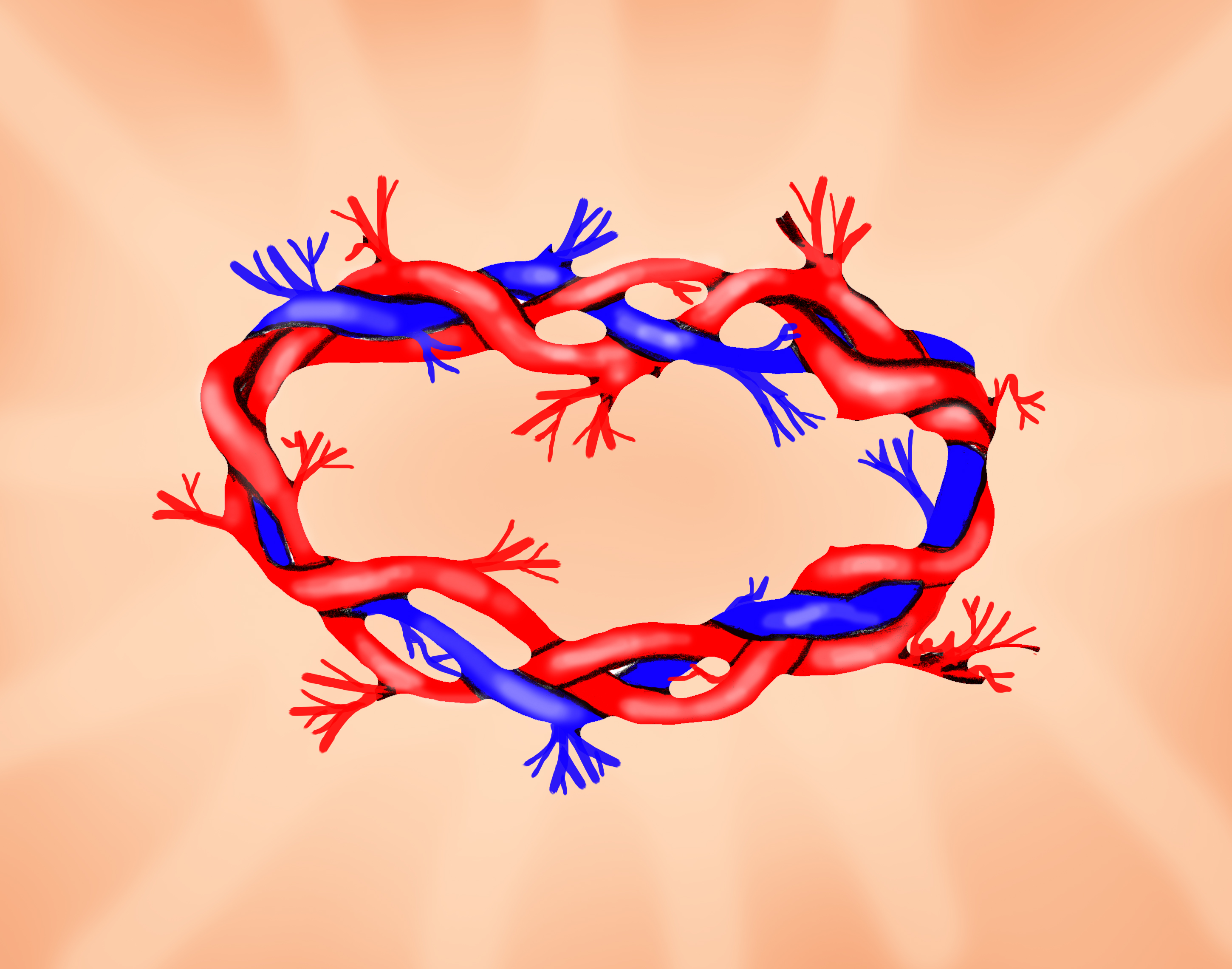

In the interview below, we discuss “These Bodies Lacking Parts,” a poem that brings us into the world of Michelangelo and the Renaissance anatomist Vesalius. They venture into the human body, Michelangelo for art and Vesalius for science. The poem is carefully researched, referencing the techniques the two used in their craft, and through that specificity becomes a meditation on how we produce knowledge, create images, and relate to our bodies. With its powerful visuals, the poem allows us to see the famous Last Judgment with new eyes, the “cochineal red” touches on the drapery and Michelangelo’s flayed self-portrait, “face/elastic, lacking eyes or mass.” As we learn that Vesalius took his bodies “fresh/from the Paduan gallows,” we then ponder the visual culture of the Renaissance anew, the grisly work of early anatomy opening the gateway for sublime, often beautiful, images.

Villanueva also discusses the sonic quality of words, his interests in Radiohead, art history, and paleontology, and the political and historical stakes of poem-making.

These Bodies Lacking Parts

With raw sienna crushed by fist

in mortar, umber ground

to tender shadow to flesh,

Michelangelo binds a body,

mid-thrash, to the plaster,

its death flex throwing a heel

into the sheets, a bare arm

up at the drapery tempered

with cochineal red. In this Sistine

pendentive, Judith and her hand-

maid carry the artist’s head away

on a dish, buckle at the knee

as if unable to bear fully the weight

of a skull hewn from the whole

of a man. On the mural opposite,

Michelangelo offers his skin

to the Last Judgment, hangs his face

elastic, lacking eyes or mass,

upon a martyr’s fingertips. All

around the Redeemer, bodies vault

towards the clamor of heaven, plead

with their thresh and flail to render

themselves apart from the damned,

rowed towards a waiting maw.

*

These are the men Vesalius halves

and digs into: criminals fresh

from the Paduan gallows, gifts

of the executioner’s axe. Unfolding

the heads of petty thieves, he laces

what nerves and veins he finds

within their sutures into a crown

shooting skyward. He figures

a new man from their bared

tributaries, writes of arteries

as latticework. When the anatomist

poses for his portrait, he instructs

apprentices to draw him directly

from nature, beside a body opened

at the wrist, his fingers gracing

the exposed vessels of the lower arm.

This poem, first published in Diagram magazine, appears in Reliquaria.

What struck me first in reading the book was the vocabulary. It became a world: something engrossing and separate from my daily experience. What were you reading, looking at in the process of writing this book?

I’m going to confess that in some ways that was a worry of mine. There were conversations with friends, in workshops, that it might even be overly learned, or esoteric. There was a certain point where I just had to own that, what I’ve always been drawn to—the feeling that poetry can take you somewhere outside your daily vocabulary.

I used to want to be a paleontologist when I was a kid, and then a doctor. I’m always drawn to the names and taxonomies of the body, species. I took Latin in high school, so something about the sound of Latinate words draws me. But that’s what prayers do—being these incantations, you conjure up things. I’ve always admired work that can be omnivorous, that takes from different things.

We think scientific naming is so calculated and empirical, but it’s not. This bone is broad like the sea, and sacred, so you name it the “sacrum.” There’s all this poetic language in how we piece the body together.

I’ve seen you read a couple times now, there’s a quality of prayer or beckoning in the way you read. How much does the sonic part of the work come in to your process?

The reverb test is a good one. For some poems, it’s a line that resonates over and over again. There’s never a poem that isn’t read out loud at some point, whether it’s that first seed or 95% finished.

One of my first workshops was with Sonia Sanchez. There’s a phrase she said that never left me, which is, “Your ear catches what your eye can’t.” You get so fatigued looking at a line, the ear tells you when the breath is over, or if there’s a compelling sonic valence you want to rest on.

Then I starting going to spoken word events and slams, and I saw people memorizing poems and screaming and wailing them, and also being very tender. I needed that somehow.

Did you ever do slam yourself?

I was the sacrificial poet a couple times at Bar 13 [for the louderARTS Project’s reading series] but I was never a competitor. I was there absorbing, admiring it, trying to metabolize it. Since moving to London, I find that what sustains me are my new friends who have come through the ranks of spoken word. You take it off the page and make something in the air—it’s a primal relationship with poetry that I want to adapt.

In the book, there’s personal history, Greek mythology, Christian history, and you draw on Luis H. Francia’s History of the Philippines: From Indios Bravos to Filipinos. What’s the role of history in these works?

I think it’s rooted in my attraction to things like paleontology and the charting of how things came to be. There’s a lot of that in scripture, too. What we inherit from those who come before us. In Reliquaria, I’m preoccupied with the ways the variables change, but these core tensions run through them.

I’m interested in putting a colonial history of conquistadors, invaders, coming to the Philippines and indoctrinating the people, against contemporary resistances. It’s a spiraling around and into everything.

When I read a book like Luis’s—spirited sometimes sarcastic, always loving—it’s a history of the country that forms my identity even though I was born in Jersey City. I compare it to what my parents tell me about home. It’s a sorting process: how are all these histories part true? How do these speakers situate themselves when these beliefs clash? We can’t escape colonization, history. As Filipino Americans you can’t. It’s there, fraught, and also deeply beautiful.

There’s a lot I don’t understand. Part of writing poetry is finding what’s supposed to make sense doesn’t.

I studied art history, and one thing I appreciate throughout the book is the art history: Damien Hirst, Delacroix, Caravaggio, Carpeaux. What draws you to certain visual artworks?

I think it’s the gore. Judith beheading Holofernes, St Bartholomew carrying his own skin in the Sistine Chapel frescoes, (which is a bizarre self-portrait of Michelangelo himself), Ugolino’s torsion and torque—all are simultaneously beautiful and awe-inspiring and terrifying. Our ability to make art embodies something paradoxical: we want to memorialize the terrible things we do to each other, and our capacity to create them is unique to us.

I studied art history in college as well, and remember seeing Caravaggio for the first time and not knowing what to do with myself. At one point I had this thought of writing a book of sonnets all related to Caravaggio, which you see in four poems towards the end of the book. I also remember seeing the word chiaroscuro, and thinking what a weird word. Tenebristic. I’ve never been able to shake those two terms, concepts.

“These Bodies Lacking Parts” comes right after this intimate poem about your wife drawing a model, you composing a poem about her body, the last lines of the poem “No one will even know/ this is you. The light will blank out your face.” In both poems, art is a process of undoing people, translating the visual to the word and vice versa. What were you thinking about that process of capturing people?

It’s always incomplete, right? You can’t fully capture the world. The capture is interrupted by your own biases, affinities. For me, maybe it favors the grotesque, the bloody. How Catholic is that? The reminder of mortality.

That’s a sad thing, but at the same time it speaks to the responsibility as the art maker to own it. Sometimes what’s left out, the mystery, is more harrowing or compelling. They talk about the Nike of Samothrace that way—what would be lost with her head or arms present. Or, take Rilke spinning around the torso of Apollo, longingly, because there is so much missing from it. Poetry and art making are about taking away as much as adding to.

What was your process in making this poem?

Andreas Vesalius is talked about here and in “Sacrum,” the first poem in the book. Some time around 2006, I stumbled upon his De humani corporis fabrica, On the Fabric of the Human Body, and I just spent months flipping through the scans of that book, looking at the illustrations. I went to the library and looked at the history of that book. The language, the ornate, Latinate way he described the body haunted me.

And much like “In Memory of Xiong Huang” [about a disappeared person from China who appears in an exhibition of bodies], I was thinking: Where did he get these bodies? It’s not addressed in his book. When I discovered that many of them were criminals, I started writing about that.

These used to be two separate poems. They feel like two incomplete pieces that, put together, feel like a complete thing. Two joints, that when joined, become that whole. I remember hearing about an interview that Thom Yorke gave where he suggested that “Paranoid Android” was made of two or three songs that didn’t work independently, so they played them together. So I was figuring out if these two parts belonged to each other, whether I could bind them in a way that wouldn’t flatten their relationship—more like a key change or tempo change.

A couple lines in the poem stuck out to me, taking common art words, and transforming them. Toward the beginning, “Michelangelo binds a body” and, towards the end, Vesalius “…instructs/ apprentices to draw him directly/ from nature…” Draw here can also mean take, pull from. Is there always violence, taking, in the artistic process?

That’s a mind-fuck of a question. [Laughs]

Binds and draws—the first has a kind of pressing, tying motion; draws has both at the same time. When pencil hits page, it brings graphite, and then to draw from is to pull away. Either way, there is activity. Art making, poem making, the act of describing, is active, is pulling and pushing.

John Berger describes this quite a bit, as an artist himself: how sketching or painting commemorates an instant, as well as the process of drawing or painting that instant. Read his essay, “Drawn to That Moment” and try to follow his argument; it contorts your head.

There is a violence to it, but not a serrated one. If violence is just a force on something else, I think it’s inevitable. That process of creation mesmerizes me when I look at the work of other people.

Sometimes people create another kind of violence with their work. They invade or make a space unsafe because they don’t recognize the violence they do to another’s experience, a kind of ahistorical or predatory relationship to the world. I hope my poems don’t work that way.

Maybe the question is how to understand violence not as one blanket force, but a nuanced part of what we do.

It’s a process of noticing, paying attention to what exists, placing it in conversation with the rest of the world as you know it, and locating yourself in it. That’s the process of binding yourself, then drawing yourself.

There’s another verb in this poem, where he offers his skin to the Last Judgment. I think that triplet move is what I’m thinking as how writers, artists, teachers, critics, approach the texts that matter to us: you’re bound to them, you’re drawn to them, and you have to offer yourself to them. They don’t just relate to you, there’s no equal sign, some false equivalence. These are the three maneuvers you make, whether you know it or not. You’re bound, you’re drawn, you offer. That’s something I want to keep bringing to what I write. That’s what moves me so viscerally about the poems I admire: the speaker is bound and drawing to and offering herself or himself to the work.

R. A. Villanueva’s debut collection of poetry, Reliquaria (U. Nebraska Press, 2014), won the Prairie Schooner Book Prize. His honors include the inaugural Ninth Letter Literary Award and fellowships from Kundiman and the Asian American Literary Review. New work is forthcoming in The Wolf (UK), Crazyhorse, and Five Points, and his writing has appeared in AGNI, Gulf Coast, Virginia Quarterly Review, and elsewhere. A founding editor of Tongue: A Journal of Writing & Art, he lives in Brooklyn and London.

Purhcase the book or read excerpts at the U. Nebraska Press website. Visit Villanueva’s website or follow him on Twitter @caesura.